What do I mean by being absent? I’m referring to time when you’re not on the receiving end of someone’s output. This could mean an in-person conversation, watching a video, listening to the radio, reading anything, playing a video game—really anything where your mind is occupied with something others want you to receive.

You might be asking “But aren’t we always receiving input if we are awake and our senses are functioning?” Having zero input might be something like meditation or sensory deprivation—but I want to talk about removing input from other people, where our mind is occupied with someone else’s ideas, thoughts or creations.

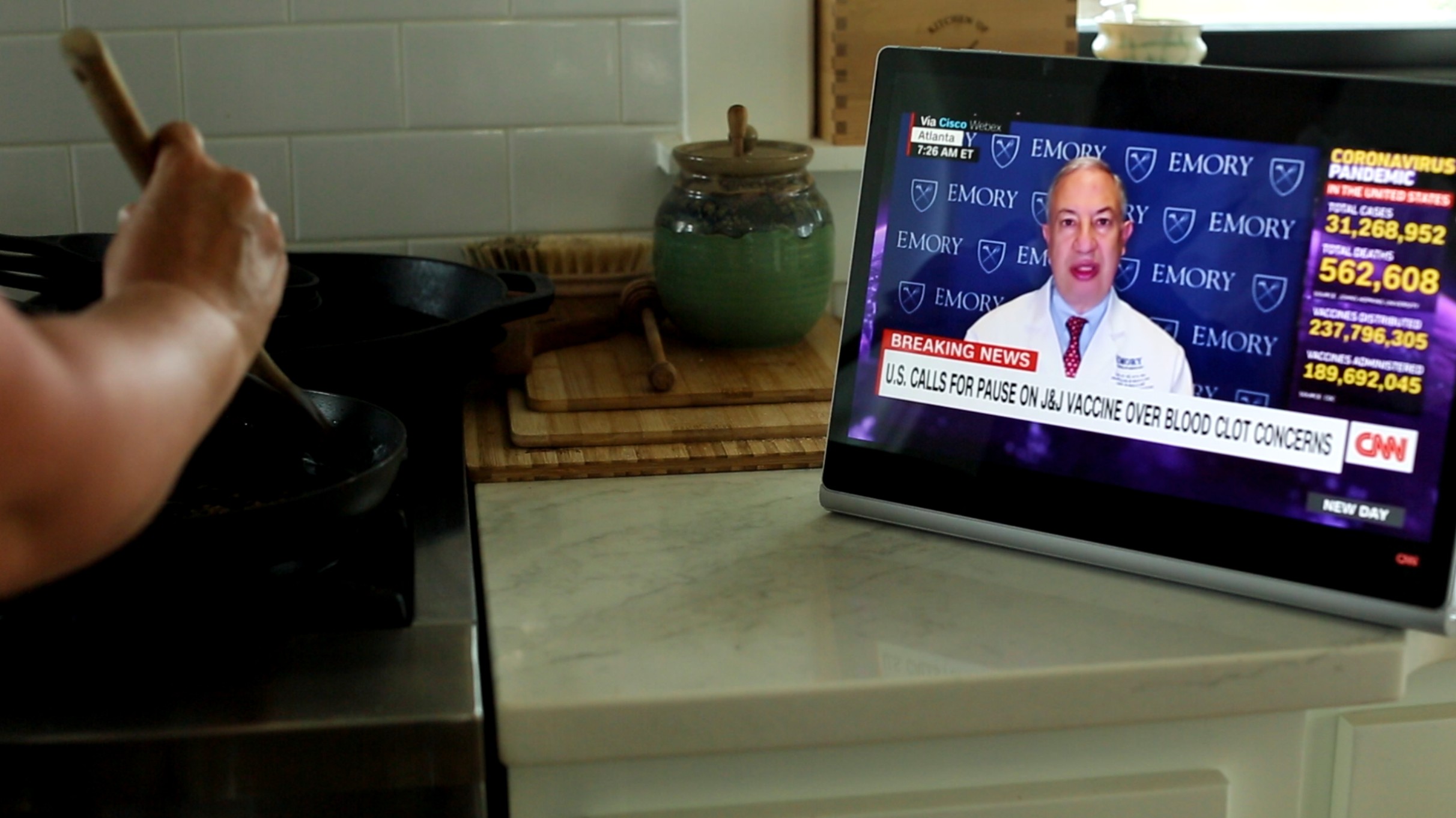

We live in an era of complete media saturation. We can spend our entire day receiving media input from TVs, smartphones, radios or computers, not to mention what we directly receive from real people (at least real people offer opportunity for dialogue).

We live in an era of complete media saturation. We can spend our entire day receiving media input from TVs, smartphones, radios or computers, not to mention what we directly receive from real people (at least real people offer opportunity for dialogue). While instant access to information and educational how-to content have provided great opportunities for people with a desire to learn, this instant access has extended to every other kind of media, including mindless and addictive entertainment, media propaganda, advertising, pornography and everything else the internet has to offer.

We develop habits around this consumption, allowing our brains to shut off and go on autopilot. Content creators are given free reign over our minds for a time. It’s “relaxing,” insofar as we’re relaxing our brains, and letting down our guard.

Many people get uncomfortable if they aren’t being constantly stimulated by some form of media. And now with media being so convenient, there’s almost zero barrier to consumption: We just pull our phone out, flip on a TV, turn on the radio or whatever media device is within reach.

Let’s imagine removing that media input, and staying alone with our thoughts. What have we been missing by never allowing these moments of absence?

How to Get Started

At first, what we’re missing will vary for different people. If you haven’t spent much time alone with your thoughts, it can feel terrifying, depressing, or boring. It can feel unnatural after years of staying on autopilot with media input. You might find it helpful to physically occupy yourself with a simple task when trying to stay absent: Go for a walk, do some yard work, maybe clean the house. Do something that will provide some time and space to think.Allow your mind to decompress and process. If we’re constantly absorbing input, we leave little time for our brains to organize our thoughts. How can we form our own opinions about things if we don’t give our minds this time to consider? The providers of mass media would rather you not form your own opinion, of course—they’d rather you just take their word for things and feel what they want you to feel—Get out of the flow of the media narrative, and give your brain some absent time.

We can reduce a lot of anxiety with absence. By breaking away from the constant onslaught of media input, we can put our life back into perspective. The mass media has a way of convincing us we need to care deeply about everything they’re throwing at us. They’ve selected a very specific subset of stories to share, painting their desired picture. Our minds will weigh these stories along with our real life events, and we’re likely ending up with a disproportionate ratio of things we shouldn’t care about. The less we consume of this media, the healthier our picture of our life will become.

There are many moments in our day that can benefit from small doses of absence: When driving alone in the car, choose to keep the radio off. Spend some time with your thoughts. When on the toilet, or in line at the coffee shop, don’t get on your phone. It’s sad to see so many restaurants, gyms and bars with TVs running nonstop. Guest’s eyes inevitably wander up to them and get stuck. If you’re going for a walk, instead of listening to music, podcasts or audio-books, spend that time with your thoughts.

Creativity can not exist without absence. The creative mind requires time to invent anything new. Of course artists draw on inspiration from others, but at some point the artist must stop being inspired, and must start creating. I’ve sensed a decline in creativity in music, movies and books, and it’s no surprise: People are spending too much time receiving, and not spending enough time alone with their thoughts to create.

Game of Thrones and Ancient Computers

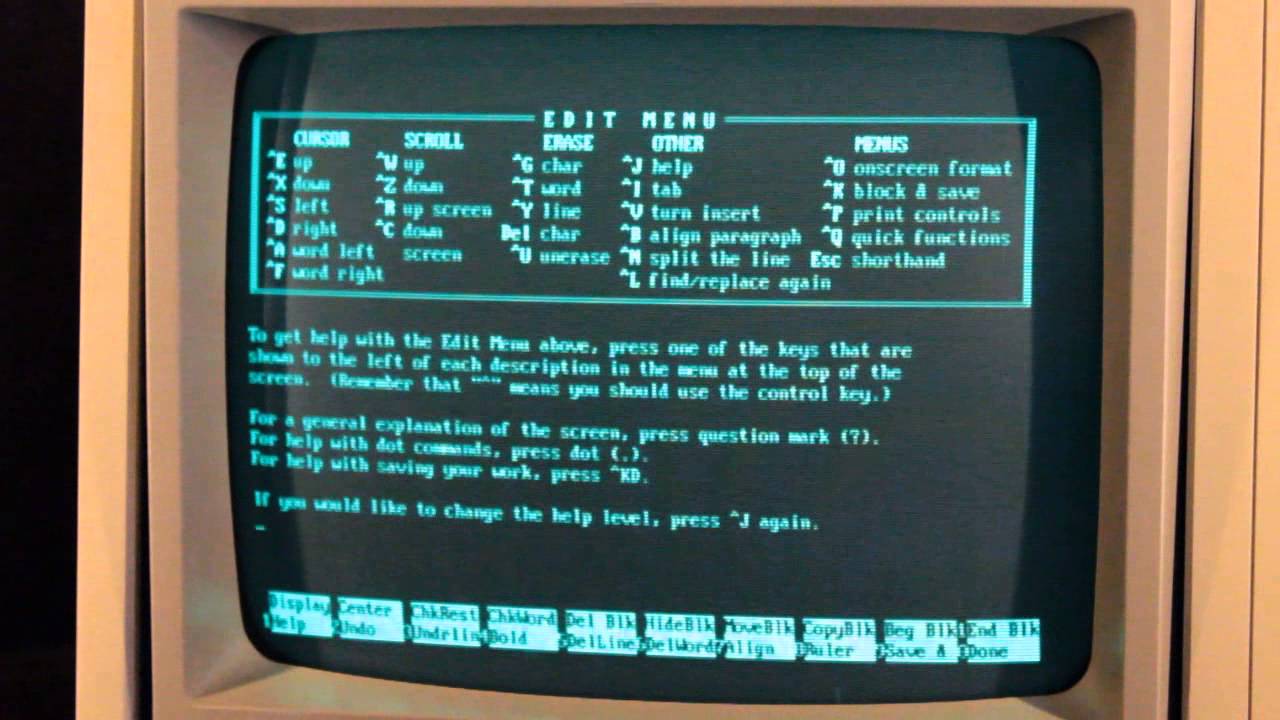

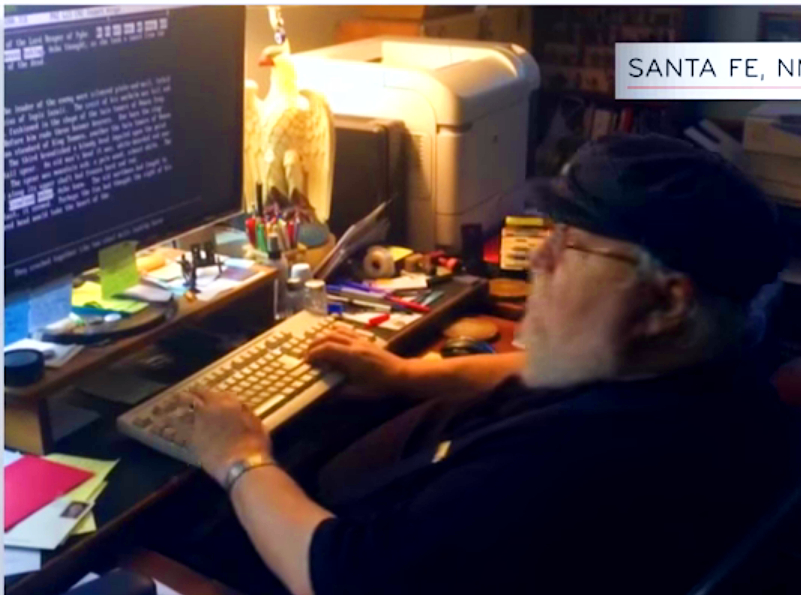

George R.R. Martin, author of the Game of Thrones book series, writes his books on an ancient DOS word processor called Wordstar 4.0 [1]. If this is before your time, Wordstar 4.0 is a monochrome, bare-bones text editor from the 1980s, but does everything needed to write a book. It doesn’t have an internet connection, so the author must save his work to floppy disk or internal hard drive. When complete, the work must be transferred off this machine via floppy disk to a more modern computer for editing and publishing.

George R.R. Martin, author of the Game of Thrones book series, writes his books on an ancient DOS word processor called Wordstar 4.0 [1]. If this is before your time, Wordstar 4.0 is a monochrome, bare-bones text editor from the 1980s, but does everything needed to write a book. It doesn’t have an internet connection, so the author must save his work to floppy disk or internal hard drive. When complete, the work must be transferred off this machine via floppy disk to a more modern computer for editing and publishing. George R.R. Martin, whether intentionally or unintentionally, discovered a way to protect his creativity. He claims he uses the DOS word processor because it’s all he needs, but I believe the benefits he receives are much greater, and the creative success of his work reinforces this. He is protecting his concentration and preventing distractions from emails and outside messages, while also removing temptations that a that a modern, multitasking computer would include. He’s avoiding even the consideration of context-switching, by using a machine that is incapable of multitasking.

Of course he has another modern computer, but he quarantines it to specific, necessary uses. When measured in bytes, a book is relatively small in size: Several could fit on an old floppy disk. But the creative value can be huge, and an old lumbering DOS machine is no impediment to writing. In George R.R. Martin’s case, he has used it to maintain control of his creative life.

I suspect George R.R. Martin has been doing things this way for long enough that he’s developed good habits that allow him to reach the necessary creative depth and isolation required to write such complex stories. He is old enough to have written on this kind of DOS software since it was new, an experience young people won’t be able to share. Martin’s habits weren’t something he had to force: He simply stuck with the machine that worked for him since the 1980s.

I suspect George R.R. Martin has been doing things this way for long enough that he’s developed good habits that allow him to reach the necessary creative depth and isolation required to write such complex stories. He is old enough to have written on this kind of DOS software since it was new, an experience young people won’t be able to share. Martin’s habits weren’t something he had to force: He simply stuck with the machine that worked for him since the 1980s. In The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains by Nicholas Carr [2], the author describes an experiment with a travel brochure. Two groups were given an identical brochure, with one group receiving it in plain text and images, and the other with the same content, but with hyperlinks in the text, just as you might see on a website. After reading the brochure, the two groups were tested on their comprehension of the content: The group who read the article without hyperlinks consistently scored higher in comprehension. The mere existence of the hyperlinks in the text reduced reader comprehension, whether the reader clicked on them or not. This may sound strange. Each time the brain encounters a hyperlink in the text, it has to consider whether to change course and click the link. This small break in focus, usually compounded several times through an article, causes a measurable decrease in comprehension.

Similarly, reading on a device such as a tablet reduces comprehension and attention span just by the fact that you have access to other distractions on the device. The lack of isolation makes it harder to stay focused on the text.

Writing Music

I’ve been writing music since I was 12. While I don’t write as much as I’d like these days, it’s a good barometer for whether I have enough absent time to create something new. When I think back to writing music, I recall the initial time spent experimenting and hashing out ideas. After that the process would shift: I would then have an idea rattling around in my head, where I’d be considering it in those little absent moments throughout the day. I would come up with new lyrics or musical ideas while driving home from work, sitting on the toilet, or somewhere else in between activities. Then I’d try the new ideas out at home when I could get to an instrument.I often wonder how different my early creative life would have been if I’d had an iPhone. Would I have written half the songs? Would they have been less developed? I ingrained good habits around my creativity, which thankfully stuck with me (for the most part) once the smartphone arrived. These days I do have to be mindful of my smartphone usage—but I try to protect these absent moments, knowing it’s where creative thoughts can emerge.

The benefits of absence on our creativity extends beyond the obvious artistic pursuits of music, writing and visual arts. When we take the time to be absent and consider things, we develop new insights and opinions: We are actively crafting our personality. Without this absent consideration, a person is only left with the opinions offered by others in their lives, and the media.

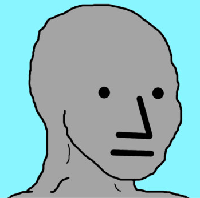

NPCs

Recently a meme became popular where people are depicted as “NPCs,” short for Non-Player Characters. In video games, a non-player character is an entity that the computer controls, usually not very rich in personality, and limited to some basic functions. The NPC meme is an observation of how many people behave as if they are non-player characters, with no unique personality or opinions, apart from the collective, mass-media narrative that surrounds us. This meme succinctly summarizes the dangerous consequences living life completely engulfed in the mass-media narrative, never allowing for absent time away to form opinions and develop a unique personality.Humans have a deep, instinctual fear of being shunned from “the group.” In our ancestral environment, separation from our group, usually of about 50-200 people, meant certain death. Finding a new group was unlikely, and a person would likely starve or become prey.

Now this fear acts as an impulse to constantly stay in the flow of the group narrative, which is today controlled by a small handful of massive corporations. They drive specific ideas and viewpoints, hammering their audience’s minds from all angles through television, radio, major news sites and publications. It’s no wonder the NPC meme emerged in this ever-presnt-media environment, as more people spend less and less time in absence away from their narrative.

What Could I Possibly Have To Say?!

In my 20s, I took piano lessons from a great teacher who was not much older than me. He had an incredible repertoire, and was a very gifted performer. I remember chatting with him after one of his concerts, asking if he’d written any music of his own. He waved his hand, exasperated, and said “What could I possibly have to say, compared to all of the incredible music that has already been written?!” I think this is a common sentiment among people who have spent most of their time receiving input from the world, and have neglected to balance that with time creating their own output.When people start lifting weights, they usually understand it’s a bad idea to compare yourself everyday to Arnold Schwarzenegger: You only compare yourself to what you were yesterday. The same should be true for your creativity. Only compare yourself to your creative output from yesterday.

Is This Input, Or Output?

As you go through your day, for each thing you do, ask yourself this question: Am I receiving input from someone else in this moment, or am I outputting something? Picture it as a spectrum: Some activities, such as folding the laundry aren’t exactly like painting the Mona Lisa, but they are a form of output. Similarly, reading your email in the morning isn’t as bad as vegging out in front of the TV for hours, but it is a case where you’re receiving input. When you start observing your actions through this lens, you’ll be able to spot excess input time and hopefully make changes to reclaim some absence, and creative output.Our goal should be to build new habits around absence and creativity. Start making it routine to keep the media devices off and protect those moments when you have time to think. And as George R.R. Martin shows us, we should find ways to protect our creativity, erecting barriers between our creative process and the endless temptations waiting for us on almost every electronic device.

If we were to look back over our lives on our death beds, would we even remember the time spent receiving input from the world? Or will our output be what mattered? In order to take actions, we must first have an original creative impulse, something that can only emerge when our minds are given an increasingly rare gift: Absence.

1. George Martin on his DOS Word Processor

2. The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains by Nicholas Carr